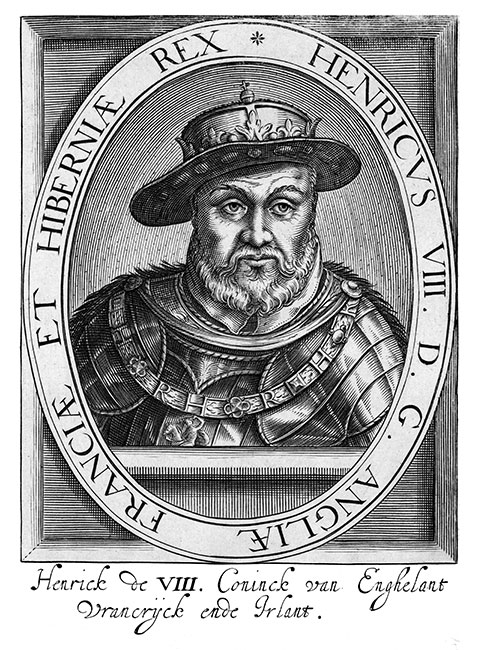

Text below taken from the Biographie universelle des hommes qui se sont fait un nom by F.X. Feller. - 1860

Automatic translation via Deepl

HENRI VIII, son and successor to Henry VII, King of England, ascended the throne in 1509. At his death, his father's coffers were filled with 2 million pounds sterling, an immense sum which would have been more useful if circulated in trade. Henry VIII used it to wage war. Emperor Maximilian and Pope Julius II had formed a league against Louis XII. The English monarch joined at the pontiff's request. He broke into France in 1544, won a complete victory at the Journée des Éperons, took Thérouanne and Tournay, and returned to England with several French prisoners, including the knight Bayard. At the same time, James IV, King of Scotland, entered England ; Henry defeated and killed him at the battle of Floddenfield. Peace was then concluded with France. Louis XII, then widower of Anne of Brittany, could only have her and Henry by marrying his sister Marie ; but instead of receiving a dowry from his wife, as kings and private individuals do, Louis XII paid one. It cost him a million ecus to marry his conqueror's sister.

Henry VIII, having brought this war to a happy conclusion, soon entered the wars that were beginning to divide the Church. Luther's errors had just broken out. The monarch, aided by Wolsey, Gardiner and Morus, refuted the heresiarch in a work which he presented and dedicated to Leo X (some authors claim that this book was entirely the work of the famous Fisher). This Pope honored him and his successors with the title of Defender of the Faith : a title he had been seeking for 5 years, and which he did not deserve for long.

At the London court, Henry fell head over heels in love with a girl full of wit and grace. Her name was Anne de Boleyn. This girl set about irritating the king's desires, and robbing him of any hope of satisfying them until she became his wife. Henri had been married for 18 years to Catherine of Aragon, daughter of Ferdinand and Isabella, and aunt of Charles V. How could a divorce be obtained ? Catherine had first married Prince Arthur, Henry VIII's elder brother, who then gave her his hand in marriage, with the dispensation of Julius II. It was not thought that such a marriage could be incestuous, but as soon as the English monarch resolved to marry his mistress, he found it null and void, and asked Pope Clement VII to declare it so. Cardinal Wolsey, that minister so vain that he usually said the king and I, agreed with Henry. Theologians were paid to extract from them decisions in line with the prince's wishes. The Pope, strongly urged to break this union, but fearing as much to breach divine law as to displease Charles V, who wished to spare his aunt this outrage, tried to gain time, believing that reflection would bring Henry back to more reasonable sentiments.

Despairing of obtaining anything, he married his mistress in 1533, and had this so-called marriage approved by Thomas Crammer, Archbishop of Canterbury. The Pope excommunicated him, and Henry declared himself Protector and Supreme Head of the Church of England. Parliament conferred this title on him, abolished all authority of the Roman Pontiff, and had his name erased from all books ; he was now called only the Bishop of Rome. The people swore a new oath to the king, called the Oath of Supremacy. Cardinal Jean Fisher, Thomas Morus and several other illustrious figures, enemies of these innovations, lost their heads on the scaffold. Henri, taking his violence a step further, opened religious houses, appropriated their property, whose income yielded, according to Salmon, 183,707 pounds sterling, and from the spoils of the convents,

he bought pleasures that vanished with the treasures he had paid for them. Henri, accustomed to resorting to the clergy and monasteries for money, found himself reduced to situations that made him “regret the hen that laid golden eggs,” as Charles V put it, speaking of Henri's impolitic operation. Another effect of the same operation was the extreme misery to which thousands of poor people were reduced by the monasteries' alms. During Elizabeth's reign, as many as eleven bills had to be passed in order to keep them alive : a means of which the annals of England had provided no examples. Henri Spelman's book, Fatality of Sacrilege, shows both the immensity of the sums Henry collected through these impious rapines, and the incredible speed with which they were dissipated.

Although Henry declared himself against the Pope, he wanted to be neither Lutheran nor Calvinist. Transubstantiation was believed as before ; the necessity of auricular confession and communion in a single species was confirmed. Priestly celibacy and vows of chastity were declared irrevocable. The invocation of saints was not abolished, but restricted. He declared that he had no intention of departing from the articles of faith received by the Catholic Church ; it was enough to depart from them to break unity. His love for a woman produced all these changes ; but this love did not last. Touched by the beauty of Jeanne Seymour, he had Anne de Boleyn's head cut off in 1536 on the flimsiest suspicion of infidelity. When Joan died in childbirth, he replaced her with Anne of Cleves. He had been seduced by the portrait of this princess, but found the original so different that he dismissed her after six months. She was succeeded by Catherine Howard, daughter of the Duke of Norfolk, who was beheaded in 1542 on the pretext that she had had lovers before her marriage. It was on this occasion that the English Parliament passed a law as absurd as it was cruel. It declared : “That every man, who shall be informed of any gallantry of the queen, must accuse her, under pain of high treason... And : That any girl who marries a king of England, and who is not a virgin must declare it under the same penalty.”

Catherine Parr, a young widow of ravishing beauty, Henry's wife after Catherine Howard, came close to suffering the same fate as this unfortunate woman, not for her gallantry, but for her Lutheran views.

Henry VIII's last years were notable for his quarrels with France. Strange in his wars as in his love affairs, he had allied himself with Charles V against Francis I, and then with Francis I against Charles V, and finally again with the latter against the French monarch. He took Boulogne in 1544, and promised to return it under the peace treaty of 1546.

He died the following year, aged 57 after reigning for 38 years, and it is reported that, as he was about to die, he exclaimed, looking at those around his bed : “My friends, we have lost everything : state, fame, conscience and heaven. Some authors have denied this anecdote ; but if Henri did not make this comment, it is certain that he could not have made a truer one. When he died, he called Edward, son of Joan Seymour, to the throne ; and, after him, Mary, daughter of Catherine of Aragon, and Elizabeth, daughter of Anne of Boleyn, even though he had had them declared bastards by Parliament and incapable of succeeding to the crown. All those who have studied Henri with any care,” says Abbé Raynal, ”have seen in him only a weak friend, an inconstant ally, a coarse lover, a jealous husband, a barbarous father, an imperious master, a despotic and cruel king.

To paint him in a single stroke, it suffices to repeat what he said at his death, “that he had never refused a man's life to his hatred, nor a woman's honor to his desires.”

He wasted the time he could have spent studying the principles of government, either in pleasures or in vain pursuits. Blind trust in his ministers reduced him to being, for half his reign, the plaything of their interests : the other half was employed in disturbing the rest of the kingdom, flooding it with blood and impoverishing it. He ruined his subjects with criminal and extravagant profusions, and this was the least of the evils he inflicted on England. It was under this prince's reign that the dangerous disease of swine fever infested the whole kingdom.

The comments expressed here are those of the author of this 1860 biography, and should be understood as such.

![]()